*Clarke, Marcus

home

table of content

united architects – essays

table of content all sites

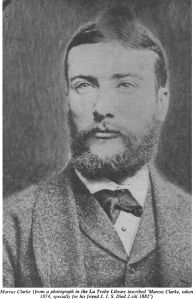

Clarke, Marcus

Australian, 1846–1881

Marcus Clarke is today acknowledged as the most notable prose writer of colonial Australia. Like many postcolonial writers, particularly those of the 19th century, his reputation did not begin to emerge until the 1950s. Even then he was critically reclaimed mainly as the author of the widely read novel, His Natural Life (1874), which dramatizes and explores in depth the horrors of the system of convict transportation. As a consequence, his considerable body of essays, written as a necessary part of the output of most authors of his time, was neglected. In addition, his essays were not collected in substantial (if still incomplete) form until the 1970s because journalism, of which they form a part, was for a long time regarded as an inferior and ephemeral branch of literature. This is ironic because in everything he wrote Clarke was the most literary of writers.

Clarke was an unwilling English emigrant to Australia, uprooted from a comfortable position in upper-middle-class English life and the prospects that went with it at an early age and under the shadow of family tragedy: his widower father collapsed physically and mentally and died shortly after Clarke arrived in Australia when he was 17, having emigrated on the advice of relations. But if he retained traces of exile, he also drew upon the resources of his fertile if mercurial temperament to meet, indeed to enjoy the challenges of post-goldrush Melbourne, which mushroomed into one of the world’s considerable and progressive cities.

One of his fellow students at Highgate School in London, Gerard Manley Hopkins, described him as “a kaleidoscopic, particoloured, harlequinesque, thaumatropic being.”

Clarke’s subject matter and styles grew out of his cross-cultural experiences and the nature of his audience. He had the background to stand apart from the pretensions and rawness of colonial society, yet he could also appreciate its vitality, nascent spirit of difference, and unconventionality. Correspondingly, as a stylist he was able to draw on the intertextuality of British, French, German, and classical literature, not simply to call up tradition but to show how writing is open to rejuvenating change when subjected to the pressures of registering the difference of a new culture.

Hence in writing of Melbourne low life in a series of essays called “Lower Bohemia” (1869), he could remind readers that the misery he was depicting “exists here,” not in Europe but in Europe transposed or translated, and that the low-life genre drew on literary models ranging from popular writers such as Paul de Kock, Eugène Sue, Beranger, Mayhew, Wilkie Collins, back to Defoe, Dante, and beyond. Clarke could call these up, not to echo them, but to appropriate them. Similarly, in “In Outer Darkness” (1869), he alluded to “the wild and fascinating life of the prairies—history told by Cooper, Aimard, Reid and a hundred minor chatterers,” for Clarke was sensitive to emerging American literature and aware of its parallels with Australian literature.

If Clarke could cast a sympathetic yet observant eye on Melbourne low life, he turned his writerly hand to a variety of subgenres and appropriate styles: satirical sketches of the rising professional classes of doctors, lawyers, and nouveaux riches in a series called “The Wicked World” (1874); an out-and-about weekly column, “The Peripatetic Philosopher” (1867–70), using the persona of a literary cynic and fringe dweller who commented on personalities, events (such as the visit of the Duke of Edinburgh), topics of the day, and set pieces, such as colonial holiday-making; write-ups of the theater, to which he was himself a contributor; sketches for a short-lived comic journal he edited, Humbug (1869–70), a rival of the Melbourne Punch; controversy in Civilisation Without Delusion (1880; later as What Is Religion?, 1895), a public debate with the Anglican bishop; and literary criticism or belles-lettres, including reviews and perceptive essays on his two main fictional models, Dickens and Balzac. He also wrote a pioneering piece on the connections between contemporary graphic art and literature, “Modern Art and Gustave Doré” (1867). An essay of art criticism, reprinted as a preface to a volume of Adam Lindsay Gordon’s poetry (1876), was influential in setting the “keynote” of Australian scenery as “weird melancholy,” with reminiscences of E.T.A.Hoffmann and Edgar Allan Poe, for Clarke’s landscapes were typically literary.

In his preface to selections from The Peripatetic Philosopher (1869), Clarke named his models as “Thackeray, Dickens, Balzac, George Sala and Douglas Jerrold”—in other words, the popular novelists and journalists of the day noted for their vivid and satirical social sketches. Clarke hoped to “equal Thackeray in satire and Dickens in description.”

He also aimed to capture what he saw in Defoe and Dickens as “the romance of reality,” the extrarealistic.

Clarke’s audience was a local one, the Melbourne metropolis, though he achieved some interstate fame in Australia and sent several dispatches to the London Daily Telegraph. Local magazines were precariously short-lived and Clarke’s main contributions were to the weekend magazines of the leading papers, the Australasian (published by the Argus) and the Leader (the Age). These were the counterparts of British literary weeklies and often had to compete with them and British magazines available at comparative prices. Some of the Australian outlets looked nostalgically back to England, others to the local, developing society, and some swung between the two. Clarke catered for both tastes. His allusiveness appealed to the one, his gusto, tinged with satire, to the other. He was criticized by some contemporaries for his “fluency,” a superficial wit and cleverness, but his stylistic flair, together with his observant eye and his manipulation of the market, made him popular and a target for envy if not an easy model to follow. These qualities insure that many of his essays repay reading today.

LAURIE HERGENHAN

Biography

Marcus Andrew Hislop Clarke. Born 24 April 1846 in London. Studied at Highgate School, London, with fellow students Cyril and Gerard Manley Hopkins. Father committed to an insane asylum, and Clarke emigrated to Australia, 1863. Worked for the Bank of Australia, Melbourne, 1864; worked on sheep stations in Western Victoria, 1865–67, then returned to Melbourne. Began contributing to journals and magazines, from 1865, including the Argus, Australian Monthly Magazine, the Age, the Leader,

Melbourne Review, Victorian Review, and the London Daily Telegraph; columnist, as “The Peripatetic Philosopher,” the Australasian, 1867–70; editor, Colonial Monthly, 1868–69, Humbug, 1869–70, and the Australian Journal, 1870–71. Cofounder, Yorick Club, Melbourne, 1868. Married Marian Dunn, 1869: six children. Worked for the Melbourne Public Library, from 1870. Went bankrupt, 1874, 1881. Died (of pleurisy and liver problems) in St. Kilda, 2 August 1881.

Selected Writings

Essays and Related Prose

The Peripatetic Philosopher (under the name “Q”), 1869

The Future Australian Race, 1877

Civilisation Without Delusion, 1880; revised edition, as What Is Religion?, 1895

The Marcus Clarke Memorial Volume, edited by Hamilton Mackinnon, 1884

Selected Works (Austral Edition), edited by Hamilton Mackinnon, 1890

A Marcus Clarke Reader, edited by Bill Wannan, 1963

A Colonial City: High and Low Life: Selected Journalism, edited by L.T.Hergenhan, 1972

Marcus Clarke: Portable Australian Authors (also contains the novel His Natural Life), edited by Michael Wilding, 1976

Other writings: three novels (Long Odds, 1869; His Natural Life, 1874 [as For the Term of His Natural Life, 1884]; Chidiock Tichbourne, 1893) tales (including Old Tales of a Young Country, 1871; Stories, edited by Michael Wilding, 1983), plays, and an operetta.

Bibliography

McLaren, Ian F., Marcus Clarke: An Annotated Bibliography, Melbourne: Library Council of Victoria, 1982

Further Reading

Elliott, Brian, Marcus Clarke, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1958

Hergenhan, L.T., Introduction to A Colonial City: High and Low Life: Selected Journalism by Clarke, St. Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 1972

McCann, Andrew, “Marcus Clarke and the Society of the Spectacle: Reflections on Writing and Commodity Capitalism in NineteenthCentury Melbourne,” Australian Literary Studies 17, no. 2 (October 1995):222–34

Wilding, Michael, Marcus Clarke, Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1977 (includes a select bibliography)

►→ back to ►→ Encyclopedia of THE ESSAY

Please contact the author for suggestions or further informations: architects.co@gmail.com;

►→home

Table of content “united architects essays”

►→*content all sites:

MORE INFORMATION ON MY OTHER SITES:

architecture, literature, essays, philosophy, biographies

Leave a comment