*Emerson, Ralph Waldo

home

table of content

united architects – essays

table of content all sites

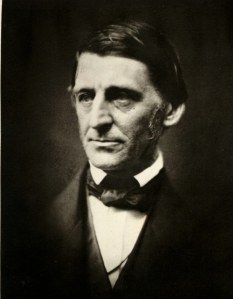

Emerson, Ralph Waldo

American, 1803–1882

Ralph Waldo Emerson is undoubtedly the premier essayist in American literary history. Over a period of 34 years he produced a remarkable series of essays which expressed a unique literary philosophy characterized by the critic Harold Bloom (in Agon, 1982) as a “literary religion” that did nothing less than express the mythology of America itself. The buoyant spirit, the philosophical light touch, and the pithy diction Emerson injected into his numerous and diverse essays signified what Oliver Wendell Holmes described (particularly in regard to “Man Thinking, or the American Scholar,” but applicable to all the essays of “the Yankee Sage”) as “America’s Declaration of Independence,” its liberation from the long shadow of the dominance of European literary styles and modes of expression. His influence on subsequent American writers— Walt Whitman, William Carlos Williams, Wallace Stevens, Robert Frost, F.Scott Fitzgerald, Willa Cather, Gertrude Stein, and others—is virtually immeasurable. Emerson provided the foundation for the emphasis on immediate experience in the thought of the philosophers John Dewey and William James and for the spirit of the pragmatic movement in philosophy in general. Emerson was at the heart of the then new focus on individuality, on what he called “the sovereign individual.” This influence even extended to the radical German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, who referred to him as “the author richest in ideas of this century.” Walt Whitman was stimulated by Emerson’s stress on the promise of the future, his respect for the “common man,” and the transformative power of the poetic spirit. He endeavored to emulate the ideal poet depicted in Emerson’s edifying essay, “The Poet” (1844).

By the time the first edition of his complete works was published in 1903–04, Emerson’s international reputation was already established. Moreover, his essays have had an unusual appeal to a large and diverse audience of general readers. This is no doubt due to the nontechnical and accessible nature of his essays. One of the leading figures in the transcendentalist movement in American literature, Emerson received recognition and serious treatment from literary critics in his own time and well into the 20th century.

And, over the last 15 years or so, he has undergone a significant, positive, and sophisticated reappraisal at the hands of a host of critics as a thinker, essayist, and poet.

He is generally considered the quintessential American writer.

Emerson’s earliest essay, Nature, was published in book form in 1836 and soon after was christened “the Bible of New England Transcendentalism.” Despite its sometimes murky metaphysical idealism, Nature clearly announced the emergence of a new voice in American literature. In addition to a celebration of the salutary value of communing with nature and the elevation of the affirmative spiritual dimension of life (through the persona of the Orphic poet), Emerson presented a condensed theory of signs that anticipated some aspects of recent semiotics. As if foreshadowing his own rich use of metaphorical imagery in his later essays, Emerson called attention to our natural reliance on analogy in ordinary language, literature, poetry, and philosophical thinking. Language is construed in Nature as pervaded by anthropomorphic metaphors and the natural world itself is

described as “a metaphor of the human mind.” There is a “correspondence” between spirit and nature that is reflected in the metaphorical language by which we describe the one in images derived from the other. This general orientation colors many of his later essays insofar as moods are metaphorically expressed and invariably suggest a metaphysics or world view.

Already in Nature Emerson’s ability to create pithy sentences, coin ingenious tropes, and produce compressed insights is apparent. Entire theories are compacted into quotable sentences: “Nature’s dice are always loaded.” “Nature is so pervaded with human life that there is something of humanity in all and every particular.” “The corruption of man is followed by the corruption of language.” Thinking of humankind’s capacity to transform the world by means of its power of spiritual transcendence, Emerson proclaims that “The kingdom of man over nature” is “a dominion such as now is beyond his dream of God.”

Edifying prose, bracing optimism, and the centrality of subjective experience, which characterize so many of Emerson’s essays, are already discernible features of his writing.

Nature is so passionately devoted to the potentialities of humankind which have not yet been realized that, as Harold Bloom has said, it might as well be entitled “Man.”

In his Essays, First Series (1841) and Essays, Second Series (1844) Emerson’s thought and expression are clear and incisive. He is the master of the aperçu, the arresting trope.

His essays have a speech-like character—several are slightly revised or polished lectures or orations, a characteristic often linked to his earlier practice, as a former Unitarian minister, of carefully preparing sermons. Emerson’s prose has a distinctive poetic quality, a prophetic tone. He displays in his essays an unusual talent for epigrammatic statement. Many of his taut sentences are eminently quotable and some of his phrases have long since passed into common English parlance: “the shot heard around the world,” “the devil’s attorney” (as “the devil’s advocate”), “a minority of one,” “a foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.” The richness of his language and the thematic content of his essays disclose his ability to compress thoughts, to attain an accessible condensation of ideas derived from a variety of disparate domains. The American critic Malcolm Cowley, in his introduction to The Portable Emerson (1981), said that Emerson created “sentences” in the Latin sense of the term: “ideas briefly and pungently expressed as axioms.” Some of his chiseled sentences are both profound and immediately persuasive, as this, from “Self-Reliance”: “In every work of genius we recognize our own rejected thoughts; they come back to us with a certain alienated majesty.” Or this, from “Fate”: “Life is an ecstasy.”

Emerson typically expresses in his essays, with striking rhetorical force and verve, a complexity of ideas that is not so much (as critics have often charged) a catena of contradictions as it is lucid perceptions and expressions of dialectical oppositions, a multiplicity of perspectives. With regard to the shifting standpoints typically found in virtually all of his essays, what Emerson said in “Montaigne” (1850) about the French prototype of the modern prose essay, the Essais, applies to his own writings as well: “An angular dogmatic house would be rent to chip and splinter in this storm of many elements.” He was quite aware of being perceived as never having constructed a conceptual foundation for the flurry of ideas he spun out in his essays; he once remarked that it was his “love of truth” which led him to abstain from propounding dogmatic absolutes. Emerson’s essays reveal a habit of provisional, experimental thinking, a flexibility of mind, an impressionistic mode of reflection clothed in metaphorical expression. He was cognizant of the limits of language and sensitive to the “unspeakable” encountered in experience which eludes precise linguistic determination or articulation.

Although he was by no means an uncritical mystic, Emerson evoked the mystery of existence, comparing it to a more perplexing version of the riddle of the sphinx. His writings often point to the wonder of the protean metamorphoses in nature. In “Circles” he celebrates, rather than bemoans, the impermanence of things, ideas, arts, of what is prized, of people, of life itself, affirming the fluidity, volatility, and circular patterns in the world. In “The American Scholar” (1837) he embraces a nature in which “there is never a beginning, never an end, to the inexplicable continuity of this web of God, but always circular power returning into itself.”

Perhaps because of his experience in delivering hundreds of lectures as a participant in the 19th-century Lyceum movement for cultural enrichment, in his essays Emerson seems to “speak” directly to the reader, to be seeking existential communication, to try to stimulate, in a Socratic manner, reflective self-consciousness. His aim is not merely to entertain or charm his readers; rather he encourages them to cultivate “self-trust,” to become what they ought to be, to be open to the internal, private, intuitive, and reflective world of experience. His oracular, “uplifting” rhetoric seems to serve, in an indirect way, a psychagogic purpose. Many of his essays are motivational exhortations to seek the good, the better, the best. Over a hundred years later they still have the power, when read in a receptive mood, to stir in the reader a powerful sense of the possible.

Aside from Nature, it is generally held that the essays of the first series show Emerson at the peak of his form, fully in control of his aphoristic powers. The works in this collection reveal a mastery of style and a confident execution of intention not readily apparent in his last collection of essays, Society and Solitude (1870). There is no doubt that style and intellectual content are synergistically combined in “Self-Reliance,” “Compensation,” “History,” and “Circles” (all 1841). However, some of the essays in the second series—in particular the striking characterization of the nature of the poetic impulse and the invocation of the liberating artist in “The Poet,” as well as the trenchant discourse on the relativity of perspective and subjectivity in “Experience”—are sprightly and convincing. In “Politics” Emerson shows himself to be the opposite of naive by hurling barbs at what is deceptive, fraudulent, and corrupt in the political atmosphere of his day.

In his portraits of various types of men in Representative Men (1850), Emerson alters his style and approach to his material somewhat and, with the exception of a surprisingly weak depiction of Shakespeare, displays a talent for literary portraiture. “Montaigne; or, the Skeptic” is a sympathetic and perceptive depiction of the man and his writings. Of the Essais Emerson tersely but aptly observes that in them we find “the language of conversation transferred to a book.” “Napoleon; or, the Man of the World” is an insightful summary of the positive and negative traits of this “thoroughly modern man” whose virtues, Emerson suggests, are almost deleted by his faults, “who proposed to himself simply a brilliant career, without any stipulation or scruple concerning the means.”

In the book-length series of essays comprising English Traits (1856), Emerson tries to do for the collective character of the English in the mid-19th century what he had done for Plato, Montaigne, Napoleon, and others in Representative Men. English Traits is a departure from his usual essay form and indicates an unsuspected versatility of style and tone. The essays comprising this collection are almost reportorial, casual, friendly toward their subject, but occasionally gently ironic, even witty.

Although the essays comprising The Conduct of Life (1860) have often been minimized in relation to the first and second series of Essays, they can be powerful, surprisingly sharp and biting pieces. Essays such as “Fate,” “Culture,” “Power,” and the barbed “Considerations by the Way” serve to dispel the traditional, projected image of Emerson as sentimental, “genteel,” “naive,” “starry-eyed,” and excessively idealistic. In these essays he concentrates more on content than on form, more on the negative aspects of existence than on the positive, more on a hard-headed realism than edifying discourses. We see in them another aspect of “the Sage of Concord,” one that emphasizes the limitation of our powers, the force of circumstances, the dangers inherent in an emerging mass society. In “Power,” we find the man called “the philosopher of the common man” praising uncommon creative artists (such as Michelangelo and Leonardo) for their energy, surplus power, and boldness. The prose hymn to “The Over-Soul” in the first series of Essays is replaced in The Conduct of Life by a decidedly this-worldly emphasis. Transcendentalism seems to be replaced by an immanent cultural idealism which nonetheless advocates a “sacred courage” in face of the terrible aspects of existence. Nature, humanity, and life are seen from a darker, but not yet pessimistic, point of view.

It is generally believed that the death of his first wife Ellen Tucker at the age of 19, the loss of his six-year-old son, Waldo, and of his two brothers—over a period of a decade— made him painfully aware of the negative aspects of existence. Nonetheless, he continued to produce incisive, carefully crafted essays. Whether his later essays were informed by painful personal experiences or not, Emerson was always prone to extend the range of his interests and adopt multiple perspectives on nature, humankind, society, and life.

Invariably he disclosed the oppositions, paradoxes, polarities, and stupendous “antagonisms” in reality.

The pungency, rhetorical power, and insightfulness of Emerson’s essays, as well as his affirmation of “the constant fact of Life” in the face of limitations, imperfections, and the vicissitudes of fate, show him to have been a sensitive, perceptive, and persuasive literary philosopher. In terms of his supreme mastery of the essay genre, the immediacy of his communication with his readers, and his ability to express profound insights in accessible language, Emerson could, with only slight exaggeration, be characterized as the Montaigne of America.

GEORGE J.STACK

Biography

Born 25 May 1803 in Boston. Studied at Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, A.B., 1821; Harvard Divinity School, 1825, 1827. Schoolmaster during the 1820s.

Married Ellen Tucker, 1829 (died, 1831). Assistant pastor, then pastor, Old Second Church, Boston, 1829–32. Traveled to Europe, 1832–33, meeting and becoming lifelong friends with Thomas Carlyle. Lyceum lecturer, after 1833. Moved to Concord, Massachusetts, 1834. Married Lydia Jackson, 1835: two sons (one died as a child) and two daughters. Leader of the transcendentalists, from 1836; contributor, 1849–44, and editor, 1842–44, the Dial transcendentalist periodical. Active abolitionist during the 1850s. Awards: honorary degree from Harvard University. Died (of pneumonia) in Concord, 27 April 1882.

Selected Writings

Essays and Related Prose

Nature, 1836; facsimile reprint, 1985; edited by Kenneth Walter Cameron, 1940, and Warner Berthoff, 1968

Essays, 1841; revised, enlarged edition, as Essays: First Series, 1847

Essays, Second Series, 1844; revised edition, 1850

Orations, Lectures, and Addresses, 1844

Nature: Addresses and Lectures, 1849; as Miscellanies: Embracing Nature, Addresses, and Lectures, 1856; as Miscellanies, 1884

Representative Men: Seven Lectures, 1850; edited by Pamela Schirmeister, 1995

English Traits, 1856; edited by Howard Mumford Jones, 1966

The Conduct of Life, 1860

May-Day and Other Pieces, 1867

Prose Works, 3 vols., 1868–78(?)

Society and Solitude, 1870

Letters and Social Aims, 1876

The Senses and the Soul, and Moral Sentiment in Religion: Two Essays, 1884

Two Unpublished Essays: The Character of Socrates, The Present State of Ethical Philosophy, 1896

Uncollected Writings: Essays, Addresses, Poems, Reviews and Letters, edited by Charles C.Bigelow, 1912

Uncollected Lectures, edited by Clarence Gohdes, 1932

Young Emerson Speaks: Unpublished Discourses on Many Subjects, edited by Arthur Cushman McGiffert, Jr., 1938

The Portable Emerson, edited by Mark Van Doren, 1946; revised edition, edited by Carl Bode and Malcolm Cowley, 1981

Selections, edited by Stephen E.Whicher, 1957

Early Lectures, edited by Stephen E.Whicher, Robert E.Spiller, and Wallace E.Williams, 3 vols., 1959–72

Literary Criticism, edited by Eric W.Carlson, 1979

Selected Essays, edited by Larzer Ziff, 1982

Essays and Lectures, edited by Joel Porte, 1983

Complete Sermons, 4 vols., 1989–91

Selected Writings, edited by Brooks Atkinson, 1992

Self-Reliance, and Other Essays, 1993

Nature and Other Writings, edited by Peter Turner, 1994

Antislavery Writings, edited by Len Gougeon and Joel Myerson, 1995

Other writings: poetry, letters, and journals (collected in Journals and Miscellaneous Notebooks, edited by William H.Gilman and others, 16 vols., 1960–83). Collected works editions: Complete Works (Centenary Edition), edited by Edward Waldo Emerson, 12

vols., 1903–04; Collected Works (Harvard Edition), edited by Alfred R.Ferguson, 5 vols., 1971–94 (in progress).

Bibliographies

Boswell, Jeanetta, Emerson and the Critics: A Checklist of Criticism, 1900–15177, Metuchen, New Jersey: Scarecrow Press, 1979

Burkholder, Robert E., Emerson: An Annotated Bibliography of Criticism, 1980–1991, Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1994

Burkholder, Robert E., and Joel Myerson, Emerson: An Annotated Secondary Bibliography, Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1985

Myerson, Joel, Emerson: A Descriptive Bibliography, Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1982

Putz, Manfred, Ralph Waldo Emerson: A Bibliography of Twentieth-Century Criticism, New York: Lang, 1986

Further Reading

Allen, Gay Wilson, Waldo Emerson: A Biography, New York: Viking Press, 1981

Atwan, Robert, “‘Ecstasy & Eloquence’: The Method of Emerson’s Essays,” in Essays on the Essay: Redefining the Genre, edited by Alexander Butrym, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1989

Bishop, Jonathan, Emerson on the Soul, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1964

Buell, Lawrence, Literary Transcendentalism: Style and Vision in the American Renaissance, Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1973

Cavell, Stanley, Conditions Handsome and Unhandsome: The Constitution of Emersonian Perfectionism, La Salle, Illinois: Open Court, 1990

Cheyfitz, Eric, The Trans-Parent: Sexual Politics in the Language of Emerson, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1981

Ellison, Julie, Emerson’s Romantic Style, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1984

Hughes, Gertrude Reif, Emerson’s Demanding Optimism, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1984

Konvitz, Milton R., editor, The Recognition of Ralph Waldo Emerson: Selected Criticism Since 1837, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1972

Michael, John, Emerson and Skepticism: The Cipher of the World, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1988

Packer, B.L., Emerson’s Fall: A New Interpretation of the Major Essays, New York: Continuum, 1982

Paul, Sherman, Emerson’s Angle of Vision: Man and Nature in American Experience, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1952

Porte, Joel, Representative Man: Ralph Waldo Emerson in His Time, New York: Oxford University Press, 1979

Richardson, Robert D., Jr., Emerson: The Mind on Fire: A Biography, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995

Robinson, David, Apostle of Culture: Emerson as Preacher and Lecturer, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1982

Stack, George J., Nietzsche and Emerson: An Elective Affinity, Athens: Ohio University Press, 1992

Thurin, Erik Ingvar, Emerson as Priest of Pan: A Study in the Metaphysics of Sex, Lawrence: Regents Press of Kansas, 1981

Van Veer, David, Emerson’s Epistemology: The Argument of the Essays, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986

Whicher, Stephen E., Freedom and Fate: An Inner Life of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1953

Yoder, R.A., Emerson and the Orphic Poet in America, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978

►→ back to ►→ Encyclopedia of THE ESSAY

Please contact the author for suggestions or further informations: architects.co@gmail.com;

►→home

Table of content “united architects essays”

►→*content all sites:

MORE INFORMATION ON MY OTHER SITES:

architecture, literature, essays, philosophy, biographies

Leave a comment