*Voltaire

home

table of content

united architects – essays

table of content all sites

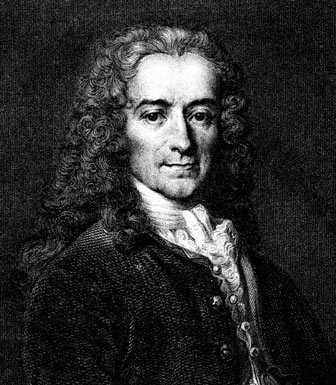

Voltaire

French, 1694–1778. When it was suggested to President de Gaulle that Jean-Paul Sartre should be sent to prison, he answered, “One does not send Voltaire to the Bastille.”

Voltaire is now remembered as a national conscience for human rights. De Gaulle’s gesture may have been generous, but it was also cautious: in 1726 Voltaire became a cumbersome prisoner visited by such a flow of admirers that the worried authorities found it preferable to free him promptly (Jean Orieux, 1978).

Voltaire enjoyed European fame early in life. His official reputation was built on poetry and tragedies (now forgotten); his influential essays were regularly condemned as seditious, and they caused him numerous imprisonments and exiles. Voltaire published them in Switzerland and in the Low Countries whenever he expected scandals.

Anonymous authorship, denied authorship, and pretense of collective authorship were some of his protective strategies. Eventually Voltaire always returned to Paris, where he finally became a member of the French Academy (in 1746), while his tragedies gave him introductions at the French court. He could have become a minister, had he not been cultivating his humorous pamphlets and essays. He also visited Frederick II of Prussia, and his entire library was purchased by Catherine II of Russia.

At the time of his 1726 stay at the Bastille, Voltaire was deemed the successor of Racine and enjoyed a budding courtier career. This imprisonment was a humiliating experience caused by France’s rigid stratification of society according to ranks of birth.

When released, Voltaire was banished to England (1726–28), where he wrote his first essays in English: the Essay upon Epic Poetry and Essay upon the Civil Wars in France, published in 1727, when he began composing the Letters Concerning the English Nation (1733). In the latter, it is apparent that he perceived fewer barriers between occupations in England, where statesmen, religious leaders, writers, and scientists could be found in the same family and treated with equal respect. Indeed, one man could freely combine such functions, as William Penn and Francis Bacon had. Voltaire believed that individuals ought to cultivate all their talents, and reacted against divides of caste and specialization.

For this reason, he later objected to d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie in which many specialists (including himself) had juxtaposed ideas. He preferred Pierre Bayle’s Dictionnaire historique et critique (1697; An Historical and Critical Dictionary), richer in its interdisciplinary insight because it issued from one mind. In his essays, Voltaire explored all branches of knowledge, and mobilized all his resources and erudition to the evaluation of human accomplishments, measured independently from national prejudice.

In addressing the English public, Voltaire adopted the stance of the ingenuous visitor judging the country according to the baffling standards of France, standards far more arbitrary, foolish, and immoral than what England had to offer. England was not free of foibles either, and English readers reflected on the historical foundations of their sociopolitical structure with Voltaire. The English Letters became a British bestseller.

The Lettres philosophiques (1734) was not merely their translation. Voltaire abandoned his playful tone but retained his humor, refusing to adopt Pascalian pessimism. French readers were meant to discover a society far more advanced than theirs in the domain of personal liberties. In France, the book was considered to be “a bomb against the Ancien Regime” (Gustave Lanson, 1966).

In the Lettres, Voltaire used both countries to give a sense of relativity to the living conditions in each regime, suggesting that ideas molded lifestyles. English political stewardship favored commerce, which benefited each citizen as well as the country’s economic health. England’s humanitarian mission was apparent in its free circulation of merchandise, and of medical and scientific knowledge. Bacon, Newton (whom Voltaire translated), and Locke, who sometimes “dares affirm, but also to doubt,” are the founders of experimental science which deduces from the objective world instead of fitting it into a conceptual mold. Voltaire’s enthusiasm for English literature (Shakespeare, Swift, Pope) echoed the admiration he felt for Milton in his Essay upon Epic Poetry, and it paralleled the relationship of experimental science to nature: the poetical genius of England resembles a strong, uneven tree which would perish under strict geometrical pruning, just as a French geometrical hierarchy would kill the prosperity and strength produced by England’s free societal system. From then on, the Voltairean essay may be understood as an attack against erroneous or limiting thoughts.

In the 12th letter, Voltaire introduced a concept of history which he developed in his most important essay, the Essai sur l’histoire générale et sur les moeurs et l’esprit des nations (1756, 1761–63; Essay on the Manner and Spirit of Nations, and on the Principal Occurrences in History), begun in June 1741 as history lessons for Madame du Châtelet.

Early versions were shared among Voltaire’s friends, and one was published in 1753 without Voltaire’s approval. The Essay constitutes the first modern comparative historof civilizations, including Asia, and a history of the human mind. Instead of repeating the succession of kings and battles tied to legendary incidents, Voltaire means to discover a given society through its ideas, domestic life, arts, and monetary systems. In the events he presents, he seeks the contrast between causes and effects, rather than their relationships.

He does not write to defend a thesis: the part on America contains opposing information;

Chapter 39 includes a paragraph of questions to which Voltaire finds no satisfying answer; Chapter 51 concludes that “A reasonable mind, while reading history, is almost strictly busy refuting it.” Louis Trénard (1979) estimates that after the Essay, history was no longer a compilation, a hagiography, or a moralizing enterprise—doubt and inconclusiveness became permissible. As the king’s historiographer, Voltaire came to realize that documents are evaluated according to our best judgment, which remains relative, being reduced to our analysis of probabilities and bound by the literary category of verisimilitude. This is also the truth which the Voltairean essay seeks to explore. Like the essayist, the historian sorts through information without necessarily finding definite answers. Another innovative aspect of Voltairean history is that the chivalric hero is rejected for the “good administrator” who protects liberties in order for society to prosper. This is also his self-appointed role as essayist and his ideal for the “philosopherking.”

One of these important liberties is religious tolerance. Voltaire expressed great sympathy for tolerant England in the first eight Lettres philosophiques, reiterated in the Essay on the Manner and Spirit of Nations. The Dictionnaire philosophique (The Philosophical Dictionary), published in Paris in 1764, was immediately condemned there, in Geneva, and in Amsterdam, and was burned in the bonfire that consumed the young Chevalier de la Barre, tortured and condemned to death because he had neglected to take off his hat while passing a bridge where a sacred statue was exposed. Voltaire denied authorship of the Dictionary while secretly augmenting the volume until 1769.

His suspicion of systematic (potentially dogmatic) thinking led him to give in to the new fashion of alphabetized works: the Dictionary (called La Raison par alphabet [Reason by the alphabet] in the 1769 edition) does not display dissertations, explanations, or argumentations. His pieces are short, incisive, polemical; they are parodies, tales, meditations. In a letter of 1760, Voltaire defined it as a “dictionary of ideas,” as an intimate piece where he would consign his thoughts about this world and the next one.

Yet (even in his memoirs) Voltaire never fell into the “ridicule of talking to oneself about oneself.” He wrote to promote tolerance, to dispel mistakes, “to act.” To that end, he limits the pages of his “portable” Dictionary. He compares the Dictionary to the Bible, which would have produced fewer converts, Voltaire argues, had it been multivolumed.

Made to instruct and distract, the Dictionary may be opened anywhere and read out of sequence. Voltaire eventually introduced it as a dialogical book: it is “more useful” when “the readers produce the other half.” The allusory and brief nature of his articles encouraged readers to participate in their message. The mood of the articles (mostly anticlerical) alternates between false compliance with established norms, indignation, laughter, and ridicule, all aimed at provoking a contagious or opposing reaction.

The nine volumes of the Questions sur l’Encyclopédie (1770–72; Questions about the Encyclopedia) are the longest piece of writing by Voltaire, written and dictated when he was old and sick. The articles vary in length from a hundred words to over 50 pages. The Questions is a summation of Voltairean thought, including an important section on religion and religious history from the Dictionary and formerly in the Lettres. Voltaire adds more literary appreciations, and gathers many fragments and hitherto independent pieces on natural and political sciences, legal systems, and commerce. According to Ulla Kölving, editor of the most recent collected works edition begun in 1983, Voltaire is more of a relativist than ever and finds no certainty but in the existence of God, “master of the Universe.”

When compared to Montaigne and Pascal, Voltaire appears more optimistic about humanity and the progress of knowledge. His essays are never composed in a frame of solitude and isolation. Montaigne writes as a recluse in his square tower, and Pascal rejects society in his longing expectation for God’s kingdom, while the suggestive Voltairean essay addresses the reason and emotions of his readers, who are called upon to shape humanity’s happier destiny. Voltaire never becomes moralizing or misanthropic: his arguments and indignation always express a faith in humanity and in the possibility of earthly contentment. In the article “Genesis” of his Dictionary, Voltaire rejects the notion of a lost golden age or Paradise: he claims that if Adam was cultivating the “garden of delights” before he was condemned to cultivate his “fields,” gardener simply became farmer and his new task does not seem that much worse, nor that bad. Adam dutifully tends his piece of land, as did Voltaire, the happy Candide and Zadig.

SERVANNE WOODWARD

Biography

Born François Marie Arouet, either 21 February (as Voltaire contended) or 21 November (according to baptismal record of 22 November) 1694 in Paris. Studied at the Collège Louis-le-Grand, Paris, 1704–11; studied law, 1711–13. Secretary to the French ambassador in Holland, 1713; articled to a lawyer, 1714. Arrested and exiled from Paris for five months, 1716, and imprisoned in the Bastille, 1717–18 (after which he used the name Voltaire), for satiric writings, and 1726, for quarrel with the Chevalier de RohanChabot; lived in England, 1726–29; lived at the Chateau de Cirey with Madame du Châtelet, 1734–36 and 1737–40 (took refuge in Holland, 1736–37). Ambassador-spy in Prussia, 1740, Brussels, 1742–43, and at the court of King Stanislas, Lunéville, 1748; historiographer to Louis XV, 1745–50; elected to the French Academy, 1746; courtier with Frederick II of Prussia, Berlin, 1750–53; lived in Colmar, 1753–54, Geneva, 1754– 55, Les Délices, near Geneva, 1755–59, and at Ferney, 1759–78; visited Paris and received a triumphant welcome, 1778. Member, Royal Society (London), Royal Society of Edinburgh, 1745, and Academy of St. Petersburg, 1746. Died in Paris, 30 May 1778.

Selected Writings

Essays and Related Prose

Essay upon Epic Poetry, 1727; as L’Essai sur la poésie épique, 1765; as Essay on Epic Poetry: A Study and an Edition, edited by Florence D.White, 1915, reprinted 1970;

part as Essay on Milton, edited by Desmond Flower, 1954

Essay upon the Civil Wars in France, translated anonymously, 1727; as Essai sur les guerres civiles de France, 1729

Letters Concerning the English Nation, translated by John Lockman, 1733; as Lettres écrites de Londres sur les Anglais, and as Lettres philosophiques, 1734; edited by Gustave Lanson and A.-M.Rousseau, 2 vols., 1964, and Frédéric Deloffre, 1986; as Letters on England, translated by Leonard Tancock, 1980; edited (in English) by Nicholas Cronk, 1994

Essai sur la nature du feu, 1739

Essai sur l’histoire générale et sur les moeurs et l’esprit des nations, 7 vols., 1756, revised edition, 8 vols., 1761–63; as Essai sur les moeurs et l’esprit des nations et sur les principaux faits de I’histoire depuis Charlemagne jusqu’à Louis XIII, edited by René Pomeau, 2 vols., 1963; as The General History and State of Europe, translated by Sir Timothy Waldo, 1754; as An Essay on Universal History, translated by Mr. Nugent, 1759, revised 1782; as Essay on the Manner and Spirit of Nations, and on the Principal Occurrences in History, translated anonymously, 1780

Traité sur la tolérance, 1763; edited by René Pomeau, 1989; as A Treatise on Toleration, translated by David William, 1779; in A Treatise on Toleration and Other Essays, translated by Joseph McCabe, 1994

Dictionnaire philosophique portatif, 1764; revised edition, 1765 (and later editions): revisions include La Raison par alphabet, 2 vols., 1769, and Questions sur l’Encyclopédie, 9 vols., 1770–72; edited by Julien Benda and Raymond Naves, 1961, and Béatrice Didier, 1994; as The Philosophical Dictionary for the Pocket, translated anonymously, 1765; as Philosophical Dictionary, translated by H.I.Woolf, 1945, Peter Gay, 2 vols., 1962, and Theodore Besterman, 1971

Essai historique et critique sur les dissensions des Églises de Pologne, 1767

Voltaire and the Enlightenment (selection), translated by Norman L. Torrey, 1931

Selections, edited by George R.Havens, revised edition, 1969

Voltaire on Religion (selection), edited and translated by Kenneth W.Applegate, 1974

Selections (various translators), edited by Paul Edwards, 1989

A Treatise on Toleration and Other Essays, translated by Joseph McCabe, 1994

Political Writings (various translators), edited by David Williams, 1994

Dictionnaire de la pensée de Voltaire par lui-même, edited by André Versaille, 1994

Other writings: several works of fiction (including the novellas Zadig, 1748, and Candide, 1759), plays, poetry, and philosophical works.

Collected works editions: OEuvres complètes (Kehl Edition), 70 vols., 1784–89, and on CD-ROM (Chadwyck-Healey); OEuvres complètes, edited by L.Moland, 52 vols., 1877– 85; Complete Works (in French), edited by Theodore Besterman and others, 135 vols., 1968–1977; Complete Works/OEuvres complètes, edited by Ulla Kölving, 35 vols., 1983–

94 (in progress; 84 vols. projected).

Bibliographies

Barr, Mary Margaret H., A Century of Voltaire Study: A Bibliography of Writings on Voltaire, 1825–1925, New York: Institute of French Studies, 1929; supplements in Modern Language Notes (1933, 1941)

Barr, Mary Margaret H., and Frederick A.Spear, Quarante Années d’études

voltairiennes: Bibliographie analytique des livres et articles sur Voltaire, 1926–1965, Paris: Colin, 1968

Bengesco, Georges, Voltaire: Bibliographie de ses oevres, Paris: Rouveyre & Blond, vol. 1, and Perrin, vols. 2–4, 1882–90; index by Jean Malcolm, Geneva: Institut et Musée

Voltaire, 1953

Candaux, Jean Daniel, “Voltaire: biographie, bibliographie et éditions critiques,” Revue d’Histoire Littéraire de la France 79 (1979):296–319

Vercruysse, Jérôme, “Additions à la bibliographie de Voltaire, 1825–1965,” Revue d’Histoire Littéraire de la France 71 (1971): 676–83

Further Reading

Aldridge, A.Owen, “Problems in Writing: The Life of Voltaire,” Biography: An Interdisciplinary Quarterly 1, no. 1 (1978): 5–22

Besterman, Theodore, Voltaire, London: Longman, and New York: Harcourt Brace and World, 1969

Brumfitt, John-Henry, “Voltaire Historian and the Royal Mistress,” in Voltaire, the Enlightenment and the Comic Mode: Essays in Honor of Jean Sareil, edited by Maxine G.Cutler, New York: Lang, 1990:11–26

Ferenczi, Laszlo, “Voltaire: Le Critique historiographe,” Acta Literaria Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 16 (1974): 140–51

Ferenczi, Laszlo, “Le Discours de Bossuet et l’Essai de Voltaire,” in Les Lumières en Hongrie, en Europe centrale et en Europe orientale, edited by Béla Köpeczi, Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 1984:187–91

Lanson, Gustave, Voltaire, New York: Wiley, 1966

Lavallée, Louis, “De Voltaire à Mandrou: Études et controverses autour du Siècle de Louis XIV,” Canadian Journal of History/Annales Canadiennes d’Histoire 12 (1977):19–49

Madeleine, L.-H., “L’Essai sur les moeurs et l’esprit des nations: Une histoire de la monnaie?,” in Mélanges Pomeau, Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, vol. 2, 1987:577–92

Monch, Walter, “Voltaire et sa conception de l’histoire: Grandeur et insuffisance,” Travaux de Linguistique et de Littérature 17, no. 2 (1979):47–58

O’Meara, Maureen F., “Towards a Typology of Historical Discourse: The Case of Voltaire,” MLN 93 (1978):938–62

Orieux, Jean, Voltaire ou la royauté de l’esprit, Paris: Flammarion, 1978

Penke, Olga, “Reflexions sur l’histoire: Deux histoires universelles des Lumières françaises et leurs interprétations hongroises,” Studies on Voltaire and the Eighteenth Century 264 (1989): 993–96

Pomeau, René, editor, Voltaire en son temps, Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 5 vols., 1985– 94

Renwick, John, Voltaire et Morangiés 1772–1773, ou Les Lumières l’ont échappé belle, Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 1982

Richter, Peyton, Voltaire, Boston: Twayne, 1980

Riviere, M.-S., “Voltaire’s Use of Larrey and Limiers in Le Siècle de Louis XIV: History as a Science, an Art, and a Philosophy,” Forum for Modern Languages Studies 25, no. 1 (1989):34–53

Roger, Jacques, Les Sciences de la vie dans la pensée française du XVIIIe siècle, Paris: Colin, 1963

Trénard, Louis, “La Place de Voltaire dans l’historiographie française,” Kwartalnik Histrii Nauki i Techniki 24 (1979): 509–22

Vignery, Robert J., “Voltaire as Economic Historian,” Arizona Quarterly 31 (1975):165– 78

Wade, Ira O., The Intellectual Development of Voltaire, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1969

Walters, Robert L., “Chemistry at Cirey,” Studies on Voltaire and the Eighteenth Century 58 (1967):1807–27

Williams, David, “Voltaire’s ‘true essay’ on Epic Poetry,” Modern Language Review 88, no. 1 (January 1993):46–57

►→ back to ►→ Encyclopedia of THE ESSAY

Please contact the author for suggestions or further informations: architects.co@gmail.com;

►→home

Table of content “united architects essays”

►→*content all sites:

MORE INFORMATION ON MY OTHER SITES:

architecture, literature, essays, philosophy, biographies

Leave a comment