*Březina, Otokar

home

table of content

united architects – essays

table of content all sites

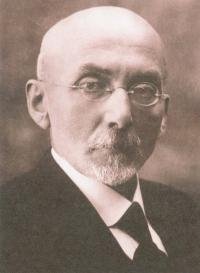

Březina, Otokar

Czech, 1868–1929

Between 1895 and 1901 Otokar Březina, the leading representative of Czech literary symbolism, published five collections of poetry. These received the attention of the foremost critics of the day and have surpassed all other literature of that period in their importance. It is no coincidence that, in addition to his poetry, Březina also wrote essays.

He soon realized—probably stimulated by his reading of Maurice Maeterlinck and Ernest Hello—that great versatility was possible in the essay form. The 1890s, when Březina’s essays began appearing in magazines, is now considered the period of some of the best Czech essayistic works. The authors of that time, particularly František Xaver Šalda, the founder of the Czech critical essay, and Březina, the most prominent personality of the poetic essay, laid the foundations of Czech essay writing.

Březina’s first book of essays, Hudba pramenů (1903; The music of the springs), and the second, Skryté dĕjiny (Hidden History)—not published until 1970, long after his death—are artistic expressions of the positive qualities of life, as well as a rich source of Březina’s artistic and aesthetic views. In both books the poet deals with fundamental questions of life and art. The essays of Hudba pramenů, written at the same time as his books of poems, make the spiritual and imaginative process of these books in a certain sense more complete, bringing them closer to the reader. Hudba pramenů is a transitional book in the sense that it represents an intermediate stage linking Březina’s artistic, aesthetic, and philosophical attitudes with those he had arrived at when he was still writing verse. In Hidden History, written mostly during World War I, the center of interest shifts from art to life. Březina’s extraordinary inner strength and certainty in such an uncertain period are clear from the fact that he did not lose his belief in humankind and his creative abilities even in the most difficult years of the war.

In his essays Březina tries, in his often overly rich metaphorical language, to express all the infinite changes of the “hidden history” of the human soul, earth, ana cosmos, which—although they take place in a latent, invisible manner, as if under the surface— nonetheless remain the moving force, and therefore the real reason, of all life. It was especially in his essays that the poet was able to find enough space to contemplate freely all the disturbing problems whose solutions became partial contributions to his efforts to achieve a synthesis; he never gave up the search for life’s inner core or its unifying meaning, its coherence with truth, beauty, and action. Březina never abandoned his attempt to penetrate—“burn through”—to the essence of things. His will for truth and consequently his will for action did not diminish in spite of his literary silence. The poet’s “eternal longing” for a harmonization of all contradictions of life and art, his longing to embrace the world in the totality of its changes and to arrive at the original unity of all cosmic beings, the compelling inner necessity to satisfy fully and truthfully the need for the essence of things, became a fully concrete expression of man trying to achieve unity with himself and the world.

Březina’s essays frequently return to the themes of social inequality, poverty, and misery. During the war the poet experienced the oppression of nations and the suffering of the masses. In his essays, from a deep conviction about the importance of a spiritual reality for humankind, grows the permanent necessity for a love which can overcome pain and suffering. There is a great longing for collectivity as well as for peace. In particular, the essay “Mír” (“Peace”) which concludes Hidden History represents the highest values in Czech literature. According to the Czech literary critic Miloš Dvořák, this is one of the most profound works to emerge from Czech literature and should be read and analyzed by all nations.

In the history of Czech literature Březina’s essays occupy an exceptional position, even though until now their importance has not been fully understood or appreciated. They are considered to be the most mature form of poetic prose of the 1890s, a time characterized by contradictions in both society and culture as well as in literature, philosophy, politics, and aesthetics. In this sense, his works also represent a search for a way to overcome and harmonize all contradictions; they are one of the solutions which, by their greatness, originality, and courage of conception, won the admiration and respect of those who were not otherwise among the admirers of the poet’s work. The mere existence of essays of this caliber is an “utter novelty” in Czech literature, according to Józef Zarek (1979), who describes them as “a work so unique that we may have difficulty in finding analogies with them in present-day literature.” Miroslav Červenka (1969) explains that these essays are meant to “present the reader with the drama of ideas themselves, the drama of human collectives, cosmic processes, and even earthly matters.” While they undoubtedly contribute to an understanding of his poetry, they are also Březina’s most systematic aesthetic confession, from which later Czech artistic and literary criticism was derived.

While the essays make understanding Březina’s poetic work easier, they are not a mere accompaniment, appendix, or explanatory commentary on the verses; they represent an autonomous work of art. From them and Březina’s correspondence we can clearly see that the poet never gave himself up to uncritical admiration of the works of the Indian poets and philosophers or Christian mystics and intellectuals of the Middle Ages. Even when he is fully occupied with the study of Maeterlinck, Hello, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Novalis, Poe, Emerson, or Solov’ev, Březina is fully conscious of his own art, preserving his independence and critical distance from the start.

The list of synonyms by which Březina’s essays were designated in the past (prose, poetic prose, philosophical prose, meditation, essayistic meditation, philosophical meditation, rhapsody, essay, philosophical essay), indicates how difficult it was to classify them appropriately and how unusual their position was in the literary world.

Whatever name we may give them, clearly Březina gave concrete support to Šalda’s principle of synthesism, trying to realize in his essays his theoretical idea of the integration of art and life, in a completely new kind of essay writing.

PETR HOLMAN

Biography

Born Václav Ignác Jebavy, 13 September 1868 in Počátky, South Bohemia. Used the pseudonyms Václav Danšovský, 1886–92, and Otokar Březina, from 1892. Studied at primary and lower secondary schools in Počátky and at higher secondary school in Telč.

Taught at schools in Jinošov, 1887–88, Nová Říše, 1888–1901, and Jaromĕřice nad Rokytnou, from 1901. Published his first lyric and epic compositions, sketches, and short stories in the journals Vesna (Spring) and Orel (Eagle), from 1886; worked on the never published and ultimately destroyed Román Eduarda Brunnera (Novel of Eduard Brunner), from 1888; his poems began to appear regularly in journals such as Vesna, Moderní revue (The modern review), Rozhledy (Outlook), Almanach secese (The almanac of secession), and Nový život (The new life), from 1892; his essays began to appear in various journals, from 1897. Corresponding member, 1913, and full member, 1923, Czech Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Awards: Czech State Prize, 1928; honorary degree from Charles University, Prague.

Died in Jaromĕřice nad Rokytnou, 25 March 1929.

Selected Writings

Essays and Related Prose

Hudba pramenů, 1903

Prvotiny, edited by Miloslav Hýsek, 1933

Prosa, edited by Miloslav Hýsek, 1933

Nové eseje, edited by Otakar Fiala, Matĕj Lukšů, and Emanuel Chalupný, 1934

Eseje z pozůstalosti, edited by Otakar Fiala, 1967

Skryté dĕjiny, edited by Josef Zika, 1970; as Hidden History, translated by Carleton Myles Bulkin, forthcoming

Esej, edited by Josef Glivický, 1988

Hudba pramenů a jiné eseje, edited by Petr Holman, 1989; revised, enlarged edition, as Eseje, 1996

Fragmenty, edited by Petr Holman, 1989 (unofficial publication)

Dokumenty, edited by Petr Holman, 1991 (unofficial publication)

Other writings: five volumes of poetry (Tajemné dálky, 1895; Svítání na západĕ, 1896;

Vĕtry od pólú, 1897; Stavitelé chrámu, 1899; Ruce, 1901), short stories, and correspondence.

Collected works editions: Spisy, edited by Miloslav Hýsek, 3 vols., 1933–39; Básnickí spisy, edited by Miroslav Červenka, 1975.

Bibliographies

Holman, Petr, and Jana Sedláková, Otokar Březina, Bibliografie 3, Brno: Státní Vĕdecká

Knihovna, 1988

Kubíček, Jaromír, Otokar Březina: Soupis literatury o jeho životĕ a díle, Brno: Universitní Knihovna v Brnĕ, 1971

Papírník, Miloš, and Anna Zykmundová, Knižní dílo Otokara Březiny, Brno: Universitní Knihovna v Brnĕ, 1969

Riess, Jiří, “Bibliografie,” in Stavitel chrámu, edited by Emanuel Chalupný and others, Prague: (in, 1941:255–74

Further ReadingČervenka, Miroslav, “Tematické posloupnosti v Březinově próze,” Česká Literatura 17 (1969):141–58

Deml, Jakub, Mé svĕdectví o Otokaru Březinovi, Olomouc: VOTOBIA, 1994 (original edition, 1931)

Fraenkl, Pavel, Otokar Březina, Prague: Melantrich, 1937 Heftrich, Urs, Otokar Březina, zur Rezeption Schopenhauers und Nietzsches im tschechischen Symbolismus, Heidelberg: Winter, 1993

Holman, Petr, K historii vzniku a vydávání Březinových esejů, Prague: Literární Archiv, Sborník Památníku Národního Písemnictví, 1989:135–85

Holman, Petr, Frequenzwörterbuch zum lyrischen Werk von Otokar Březina, Cologne, Weimar, and Vienna: Böhlau, 2 vols., 1993

Hyde, Lawrence, “Otokar Březina—A Czech Mystic,” Slavonic Review 2, no. 6 (March 1924):547–57

Jelínek, Hanuš, “Un poète de la fraternité des âmes: Otokar Březina,” Revue de Genève 2 (1929):223–36

Králík, Oldřich, Otokar Březina 1892–1907: Logika jeho díla, Prague: Melantrich, 1948

Lakomá, Emilie, Úlomky hovorů Otokara Březiny, edited by Petr Holman, Brno: Jota & Arca Jimfa, 1992

Lakomá, Emilie, “Dodatky k Úlomkům hovorů Otokara Březiny,” BOX 1, no. 1 (1994):40–47

Marten, Miloš, Otokar Březina, Prague: Symposion, 1903

Marten, Miloš, Akkord: Mácha, Zeyer, Březina, Prague: Kočí, 1916

Novák, Arne, “Otokar Březina, Obituary,” Slavonic Review 8, no. 22 (June 1929):206–09

Selver, Percy Paul, Otokar Březina: A Study in Czech Literature, Oxford: Blackwell, 1921

Slavík, Bedřich, “Březinův essay,” Archa 18, no. 4 (1930):257–78

Slavík, Bedřich, “Essay Březinův a Unamunův,” Akord 3, no. 9 (1930):374–80; 3, no. 10 (1930):403–07

Vesely, Antonín, Otokar Březina, Brno: Moravské kolo Spisovatelů, 1928

Zarek, Józef, Eseistyka Otokara Březiny, Wrocław: Ossolineum, 1979

Zika, Josef, Otokar Březina, Prague: Melantrich, 1970

►→ back to ►→ Encyclopedia of THE ESSAY

Please contact the author for suggestions or further informations: architects.co@gmail.com;

►→home

Table of content “united architects essays”

►→*content all sites:

MORE INFORMATION ON MY OTHER SITES:

architecture, literature, essays, philosophy, biographies

Leave a comment