*Berry, Wendell

home

table of content

united architects – essays

table of content all sites

Berry, Wendell

American, 1934–

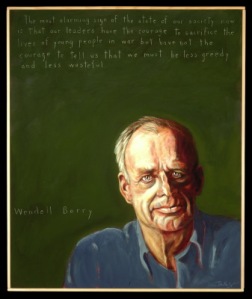

Farmer, naturalist, and conservationist Wendell Berry has published nine essay volumes and three additional nonfiction works, along with novels and poetry. His nature essays have called attention to the economic and environmental problems in modern American agriculture, especially the loss of traditional farm communities and rural culture. As a Jeffersonian agrarian, Berry has defended the moral, civic, and environmental values of the family farm. He first gained widespread recognition for The Unsettling of America: Culture and Agriculture (1977), a polemic against the excesses of corporate agribusiness.

Berry’s career as an essayist coincided with the American environmental movement, beginning with the first Earth Day in 1972. His essays have appeared in publications ranging from the Whole Earth Catalogue to Smithsonian magazine. As a contributing editor with Rodale Press from 1977 to 1979, Berry promoted the organic farming movement in essays and articles in the New Farm and Organic Gardening. A selfproclaimed generalist in an age of specialists, Berry addresses his essays to a broad and diverse audience of general readers, promoting with evangelistic fervor the values of economic and cultural self-reliance.

The early autobiographical essays, The Long-Legged House (1969) and “A Native Hill” (1969), established Berry’s roots as a Kentucky regionalist and agrarian. The long philosophical essay “Discipline and Hope” (1972) presents his criticism of the American consumer culture and calls for renewal through simplicity and self-reliance. As a farmer and writer, Berry writes out of his deep love for land and place. He offers an articulate defense of traditional farming (“A Defense of the Family Farm,” 1986) as a viable economic and cultural alternative to corporate consumerism. In “The Making of a Marginal Farm” (1980), he explains his decision to leave a teaching career in New York and return to Kentucky to farm and write. As an agrarian regionalist, Berry is both conservative and radical. His cultural conservatism (“The Work of Local Culture,” 1988) has led him to be politically radical in his opposition to the social and economic forces destroying family farms and rural communities. As a regionalist (“The Regional Motive,” 1972) who has struggled to create a wholesome economic, ecological, and moral order within his family, farm, and community, he favors economic self-sufficiency (“The Tyranny of Charity,” 1965) for the Cumberland region and opposes industrialism, urbanization, and technology (“Property, Patriotism, and National Defense,” 1984), but he sharpens his advocacy of rural life with an informed ecological vision and a clear understanding of the complex relationships among the health of the individual, family, community, and environment (“Does Community Have a Value?,” 1986). The themes of home, work, husbandry, rootedness, stewardship, responsibility, thrift, order, memory, atonement, and harmony resonate throughout his essays.

Berry’s regional loyalty has led him to speak out against the ravages of strip-mining in the Cumberland region (“The Landscaping of Hell: Strip-Mine Morality in East Kentucky,” 1965); to protest against the pollution of the Kentucky River by vacationers (“The Nature Consumers,” 1967); and to write an eloquent plea to preserve Kentucky’s Red River Gorge (“The Unforeseen Wilderness,” 1971). But the major target of Berry’s wrath has been the destructive farming practices of corporate agribusiness (“The Body and the Earth,” 1977). Berry’s ecological essays often assume an almost religious tone. In “A Secular Pilgrimage” (1972), he traces the origins of the environmental crisis to our disdain for the earth. Berry calls for a renewal of biblical stewardship in “The Gift of Good Land” (1979); promotes the idea of usufruct in “God and Country” (1990); and outlines a nondualistic natural theology that affirms the sacredness of the world in “Christianity and the Survival of Creation” (1992). Protection of wildness and careful land use are not incompatible, he argues in “Preserving Wildness” (1985).

As a social critic, Berry examines the cultural influences of industrialism and the consumer economy. He writes about the effects of corporate greed on American culture: the vulgarization of popular culture and the debasement of language; the decline of public education; the destruction of family and community life; and the degradation of the environment. He reaffirms the dignity and value of work (“People, Land, and Community,” 1983); criticizes the destructive assumptions of free market economics (“Two Economies,” 1983); praises the thrift and resourcefulness of Amish culture (“Does Community Have a Value?”); defends marriage against feminist attacks (“Feminism, the Body, and the Machine,” 1987); and protests against the exploitation of sex in American consumer culture (“Sex, Economy, Freedom, and Community,” 1992).

In his literary essays, Berry stresses the importance of regionalism, respect for language, and traditional poetic forms. He values pastoral poetry for its ability to connect us with nature (“A Secular Pilgrimage”); laments the loss of readership for contemporary poetry (“The Specialization of Poetry,” 1974); insists upon the need to protect the integrity of language to prevent cultural decline (“Standing by Words,” 1983); and praises Mark Twain, Sarah Orne Jewett, and Wallace Stegner for their regional loyalty (“Writer and Region,” 1987).

Berry is a polemical writer who emphasizes theme and argument over purely literary stylistics. More didactic than discursive as an essayist, he is nevertheless a clear and forceful writer who resembles Edward Abbey in his passionate defense of environmental concerns. Berry is also a moralist in the tradition of Henry David Thoreau, for whom simplicity and self-reliance are essential virtues. Like Thoreau, he is a writer of deep personal conviction who has articulated the social and economic principles by which he would live and write. He has striven to achieve clarity and directness in his essays by insisting upon the basic harmony among work, vocation, family, community, and nature.

One finds in Berry’s essays a continual effort to unify life, work, and art.

Berry is essentially a pastoral writer whose inspiration comes from his rural Kentucky heritage. In his essays, he celebrates the personal satisfactions of farming and husbandry.

He cares deeply about his subjects: the dignity of work; the proper care of the land; the importance of marriage, family, and community; and the continuities of history and region. Though he regrets the loss of the discipline of thrift, care, and conservation that farming teaches, most of all it is the spiritual value and restorative power of living in harmony with nature that Berry cherishes. Perhaps best known for his agricultural and environmental essays, Berry is an important social and cultural critic whose works have helped preserve the heritage of rural American culture.

ANDREW J.ANGYAL

Biography

Wendell Erdman Berry. Born 5 August 1934 in Henry County, Kentucky. Studied at the University of Kentucky, Lexington, A.B., 1956, M.A., 1957; Wallace Stegner Writing Fellow, Stanford University, California, 1958–59. Married Tanya Amyx, 1957: one daughter and one son. Taught at Stanford University, 1959–60; traveled on a Guggenheim Fellowship to Italy and France, 1961–62; taught at New York University, 1962–64, and the University of Kentucky, 1964–77, and from 1987; staff member, Rodale Press, Emmaus, Pennsylvania, 1977–79.

Awards: several grants and fellowships; Poetry magazine Vachel Lindsay Prize, 1962, and Bess Hokin Prize, 1967; Friends of American Writers Award, for novel, 1975.

Selected Writings

Essays and Related Prose

The Long-Legged House, 1969

The Hidden Wound, 1970

The Unforeseen Wilderness: An Essay on Kentucky’s Red River Gorge, 1971

A Continuous Harmony: Essays Cultural and Agricultural, 1972

The Unsettling of America: Culture and Agriculture, 1977

Recollected Essays 1965–1980, 1981

The Gift of Good Land: Further Essays Cultural and Agricultural, 1981

Standing by Words, 1983

Home Economics, 1987

What Are People For?, 1990

Harlan Hubbard: Life and Work (lectures), 1990

Standing on Earth: Selected Essays, 1991

Sex, Economy, Freedom & Community, 1993

Another Turn of the Crank, 1995

Other writings: many collections of poetry, four novels (Nathan Coulter, 1960; A Place on Earth, 1967; The Memory of Old Jack, 1974; Remembering, 1988), short stories, and a play.

Bibliographies

Griffin, John B., “An Update to the Wendell Berry Checklist, 1979-Present,” Bulletin of Bibliography 50, no. 3 (September 1993):173–80

Hicks, Jack, “A Wendell Berry Checklist,” Bulletin of Bibliography 37 (1980):127–31

Further Reading

Angyal, Andrew J., Wendell Berry, New York: Twayne, and London: Prentice Hall International, 1995

Merchant, Paul, editor, Wendell Berry, Lewiston, Idaho: Confluence, 1991

►→ back to ►→ Encyclopedia of THE ESSAY

Please contact the author for suggestions or further informations: architects.co@gmail.com;

►→home

Table of content “united architects essays”

►→*content all sites:

MORE INFORMATION ON MY OTHER SITES:

architecture, literature, essays, philosophy, biographies

Leave a comment