*Kamo no Chōmei

home

table of content

united architects – essays

table of content all sites

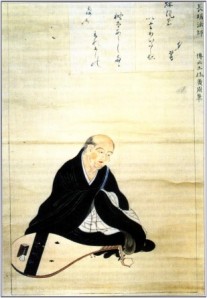

Kamo no Chōmei

Japanese, 1155?–1216

As one of the three great essayists in the tradition of classical Japanese literature, Kamo no Chōmei occupies a median in style, sensibility, and time between the other two exemplars of the zuihitsu genre—the Makura no sōshi (Pillow Book) of Sei Shōnagon and the Tsurezuregusa (Essays in Idleness) of Kenkō. In sentiment lying somewhere between the aristocratic delicacy of the former and the rapid delight in life found in the latter, the Hōjōki (1212.; An Account of My Hut) is both simple and complex, a unique mingling of style and wit in the tradition of Japanese prose. Yet during his lifetime Chōmei held greater renown for two other works that reflect not only his wide literary skill and interest, but the two primary influences on his prose—classical poetry and a deep Buddhist piety—which permeate the whole of his principal and most prized work.

Mumyōshō (1210?; A treatise with no name) is a subtle and joyous work, representing the culmination of Chōmei’s many years spent among the poetic circles of the Imperial Court. Both a study of late Heian poetics and a personal—even chatty—recollection of personalities, places, and poem-banquets, this earlier work is in many respects a look backwards to the bright, elegant world of Shōnagon and the classical era of Japanese prose. Chōmei’s skill as a poet is quite obvious—although clearly not the equal of his contemporaries Teika and Shunzei; his love of old diction and fresh images is evident in his surviving poems, and it is this mingling of old and new that becomes most manifest in the prose of An Account of My Hut. Another work written in parallel with An Account of My Hut, the Hosshinshū (12.14?; Collected tales of awakened faith), an unorthodox collection of Buddhist tales of religious enlightenment, is pervaded with Chōmei’s own

reflections of his faith. While the work should not be considered a standard Japanese essay as such, nor even typical of the compilations of his day, the masterful touches of the author are unmistakable: quick, almost fluid phrasing, a keen eye for details interior and exterior, and a passionate resignation lurking behind every sentence.

Chōmei’s reputation as an essayist, however, is due to the high substance and style of An Account of My Hut, a collocation best expressed in the single word mujō (impermanence). Just as the famous opening line bursts into syntactic flow—“The river’s flow never ends, its waters never stay the same; bubbles appear and vanish, floating among the pools, never resting: just so our world of men and their dwellings”—the supple strength of his words serves as a wellspring for the entire work, a prolonged meditation on the ceaseless flux between the human and natural worlds. Writing in seclusion, in a hermit’s small grass hut far from the political and aristocratic intrigues of the capital, Chōmei strives for a distinct degree of separation from the “floating world” of the court; his wariness at the uncertainty of human affairs is echoed in the loose, almost unconnected structure of the work and the pessimistic tone of his observations. In the miniature world of his hermitage, true pleasure emerges only from observation of the transience of nature or from the joys of aesthetic creation: playing at his harp or pondering over a line of verse. This disdain for the practical aspects of life—and the essay—is central to Chōmei’s world; neither art, word, nor nature is for the sake of instruction or the transmission of absolute truth. The phrased rapids of An Account of My Hut wander through relative mountains and valleys of human experience, only to vanish into an endless, all encompassing ocean of silence and shadow. His view of human fate is not mere pessimism: he seeks the tranquil promise of the contemplative life and the slow pursuit of artistic and spiritual perfection. At the essay’s end, Chōmei sets aside his brush—but only for a moment, for his verbal peregrinations, fixed in ink, have made him into an immortal member of the Japanese canon.

Apart from the poetic currents of his day, there are two distinct influences on Chōmei’s work: the prose of his Japanese predecessor Sei Shōnagon, and the semi-versified essays of the Chinese fu genre. The former, writing more than 200 years before Chōmei, endows him in no small part with her gift for wry observation and short, elegant phrases; his debt becomes particularly clear in his austere, uncluttered language, especially when compared with his contemporaries. From the Chinese literati such as Su Shi he absorbs both the loose structures and the poetic fancies of the fu, a literary form prone to limpid language and evanescent sensations. With these two disparate traditions of the essay before him, Chōmei fuses them to create a new style for the Japanese essayist: personal yet detached, intimate in emotion yet oblique in thought. His legacy to the essayists that follow is immense; Kenkō, among many others, is unimaginable without the lasting force of Chōmei’s observations of the transient world made permanent in a liquid tangle of tears and ink.

JOHN PAVEL KEHLEN

Biography

Born in 1155? Brought up in Kyoto; had a classical education. Played the lute and wrote poetry for the court; involved with poetry circles connected to the Emperor Go-Toba (who held the throne, 1183–98); invited to be a Fellow of the Bureau of Poetry, 1201.

Took Buddhist orders and retired from court to a hermitage on Mt. Ohara, near Kyoto; later moved to Mt. Hino, where he lived in his “ten-foot square hut.” Died in 1216.

Selected Writings

Essays and Related Prose

Hōjōki, edited by Miki Sumito, 1976, and Satake Akihiro and Kubota Jun, 1989; as Notes from a Ten Feet Square Hut, translated by F.Victor Dickins, 1907; as The Ten Foot Square Hut, translated by A.L.Sadler, 1928; as The Hō-jō-ki: Private Papers of Kamono- Chōmei, of the Ten Foot Square Hut, translated by Itakura Junji, 1935; as An Account of My Hut, translated by Donald Keene, in Anthology of Japanese Literature:

From the Earliest Era to the Mid-Nineteenth Century, 1955; as Notebook of a Ten Square Rush-Mat Sized World, translated by Thomas Rowe and Anthony Kerrigan, 1979; as Hōjōki, Visions of a Torn World, translated by Moriguchi Yasuhiko and David Jenkins, 1996

Hosshinshū, edited by Miki Sumito, 1976; as The Hosshinshū, partially translated by Marian Ury (dissertation), 1965

Mumyōshō, edited by Yanase Kazuo, 1980, and Takahashi Kazuhiko, 1987

Other writings: poetry.

Collected works edition: Kamo no Chōmei zenshu, edited by Yanase Kazuo, 2 vols., 1940.

Further Reading

Hare, Thomas Blenman, “Reading Kamo no Chōmei,” Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 49 (June 1989):173–228

Katō, H., “The Mumyōshō of Kamo no Chōmei and Its Significance in Japanese Literature,” Monumenta Nipponica 23, nos. 3–4 (1968):321–430

LaFleur, William R., “Inns and Hermitages: The Structure of Impermanence,” in his The Karma of Words: Buddbism and the Literary Arts in Medieval Japan, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1983:60–79

►→ back to ►→ Encyclopedia of THE ESSAY

Please contact the author for suggestions or further informations: architects.co@gmail.com;

►→home

Table of content “united architects essays”

►→*content all sites:

MORE INFORMATION ON MY OTHER SITES:

architecture, literature, essays, philosophy, biographies

Leave a comment