*Turgenev, Ivan

home

table of content

united architects – essays

table of content all sites

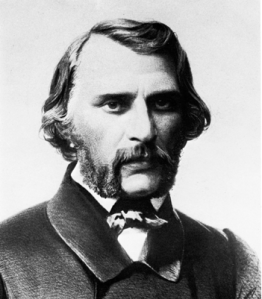

Turgenev, Ivan

Russian, 1818–1883

Apollon Grigor’ev, a 19th-century Russian critic, complained that Ivan Turgenev set no straight course and consequently was “subject to all winds, the stirrings of a breeze” and its gossamer waftings. What was a shortcoming for Grigor’ev is serendipity for the modern reader, for without a manifest ideology and program Turgenev became the sensitive eye and ear of his era. He was attuned to the most subtle changes in societal temperature and weather. Though only two of his 28 volumes of works and letters are composed of essays and other articles, these range in subject from the psychic life of a dog (“Pegaz” [1871; Pegasus]), to coverage and analysis of the Franco-Prussian War, to an appreciation of the ruins of the temple of Zeus discovered in Pergamon in 1878. Turgenev produced travel articles, reviews of literature, music, and art, cultural commentary, ethnographic sketches, reportage, reminiscences of famous friends, and obituaries, as well as a currently archaic form, the prepared speech for significant occasions—an oral essay. In a highly politicized time in Russian history the above appeared in diverse magazines and newspapers such as the Russkii Vestnik (Russian courier), Vestnik Evropy (Courier of Europe), Sovremennik (The contemporary), Novoe Vremia (New times), Spb Vedomosti (St. Petersburg news), Nedelia (The week), Moskovskii Vestnik (Moscow courier), and even the Zhurnal Okhoty i Konnozavodstva (Hunter’s and horseman’s journal).

Turgenev saw himself as living during an era of transition in Russian culture and history (Vospominanie ob A.A. Ivanove” [1861; “Reminiscences of Ivanov”]). For him Russia was a powerful nation but in an embryonic state of unformed corporate institutions and unattended tensions. He was at once very Russian and an exemplar of a European-wide high culture. Turgenev was fluent in Russian, French, and German, knew English and Italian, and read in the classical languages. So proficient was he in French that he could differentiate between the dialects of Provence and Gascony. He was well versed in the principal European traditions of literary criticism and the serious essay of social and political commentary, citing numerous French practitioners of the craft and especially valuing Gotthold Ephraim Lessing in German and Thomas Babington Macaulay in English. He was an astute critic of the arts, knowledgeable in technique, historical significance, and effect. In many respects he prefigures his younger contemporary, Walter Pater. With such scope Turgenev naturally eschewed the utilitarian notion of a writer being driven by a particular agenda or by the projection of his own ideas into his art (“Po povodu Otsov i detei” [1869; “On Fathers and Sons”]).

Turgenev’s first true essay, “Les i step’” (1849; “The Forest and the Steppe”)— published first in Sovremennik and then as an appendage to his Zapiski okhotnika (1852; A Sportsman’s Sketches)—began a tradition of reflections on the significance of human life and its meaning. It deals specifically with immutable nature, the transience of the manifest, and the obscurity of the transcendent. This theme casts a constant shadow over his dominant idealism. Like most intellectuals of the time Turgenev believed in universal progress, both material and spiritual, thus revealing his Hegelian inheritance and the fruits of his philosophical studies in Berlin. Literature (and literary criticism) to him was the royal road to understanding culture and the self. Turgenev held this belief perhaps more fervently than either Dostoevskii or Tolstoi, who themselves embraced alternative systems as well. Art for Turgenev was not so much for entertainment as it was for the education of sensibility, although there is some dissonance between his views of literature as keeper of civic consciousness (the 1860s) and intimate salon literature (1830s and 1840s), as exemplified in “Literaturnyi vecher u P.A.Pletneva” (1869; “A Literary Evening at Pletnev’s”). Scrupulously dispassionate and evenhanded in his reminiscences, he praises both Timofei Granovskii and Nikolai Stankevich for their accomplishments, though he adores the first and is cool toward the second. In “Vospominaniia o Belinskom” (1869; “Reminiscences on Belinskii”) he praises love of country while discrediting chauvinism and self-styled defenders of the motherland. In another essay Turgenev reveals a subtle psychological sense that sees the notorious Jean Baptiste Tropmann (“Kazn’ Tropmana” [1870; “The Execution of Tropmann”]) on the morning of his execution as giving a bravura “stage performance” to the assembled distinguished witnesses and thus keeping himself from disintegrating into hysterics. After the beheading none of the company feels that an act of justice has taken place.

Of the greats, Turgenev esteems Pushkin (e.g. his speech at the dedication of the monument to Pushkin in 1881, a major event in the history of Russian culture), Shakespeare (a speech at the celebration in 1864 of the 300th anniversary of Shakespeare’s birth), and Gogol’ (“Gogol’,” 1869), with a caveat for his retrogressive piety. Authenticity, enlightenment, freedom, and courage are the traits he values in the artist and the citizen. He praises Pushkin’s classical sense of measure and harmony but sees it as devalued by his contemporaries.

Turgenev lived in the post-Christian world of the intelligentsia but with the residual gift of having the Enlightenment and Christian ethics as sources of his values. He professed an aesthetic humanism which was an anachronism to many of his contemporaries. He believed that the engagement with art took the self into a meta-reality where choices, explorations, and seductions had no external constraining consequences.

The self is thereby liberated from its linear public life and becomes free to make radical choices, run risks, assume alien identities, and spar with powerful opponents. It returns from this world aware of styles and choices which are normally closed to it. Thus exploring the ambiguity and multiplicity of meaning in art makes us intellectually agile, physically elegant, and spiritually tolerant.

GEORGE S.PAHOMOV

Biography

Born 9 November 1818 in Orel. Studied at Moscow University, 1833–34; University of St. Petersburg, 1834–37; University of Berlin, 1838–41; completed his master’s exam in St. Petersburg, 1842. Civil servant, Ministry of the Interior, 1843–45. Intimate friendship with Pauline Garcia-Viardot, traveling to France with her and her husband, 1845–46 and 1847–50. Had a daughter by one of his serfs. Arrested and confined to his estate for writing a commemorative article on Gogol’s death, 1852–53. Left Russia to live in

Western Europe, 1856, first in Baden-Baden, then Paris with the Viardots, 1871–83.

Doctor of Civil Laws: Oxford University, 1879. Died in Bougival, near Paris, 3 September 1883.

Selected Writings

Essays and Related Prose

Literaturnye i zhiteiskie vospominaniia, 1874; revised edition, 1880; as Literary Reminiscences and Autobiographical Fragments, translated by David Magarshack, 1958

Other writings: many novels (including Zapiski okhotnika [A Sportsman’s Sketches], 1852; Rudin, 1856; Dvorianskoe gnezdo [A Nest of the Gentry], 1859; Nakanune [On the Eve], 1860; Ottsy i deti [Fathers and Sons], 1862), novellas (including Pervaia liubov’ [First Love], 1860), stories, plays (including Mesiats v derevne [A Month in the Country], 1869), poetry, and correspondence.

Collected works editions: Polnoe sobranie sochinenii i pisem, 28 vols., 1960–68;

Polnoe sobranie sochinenii i pisem, edited by M.P. Alekseev, 30 vols., 1978.

Bibliographies

Waddington, Patrick, A Bibliography of Writings by and About Turgenev Published in Great Britain up to 1900, Wellington, New Zealand: Victoria University of Wellington Department of Russian, 1985

Yachnin, Rissa, and David H.Stam, Turgenev in English: A Checklist of Works by and About Him, New York: New York Public Library, 1962

Zekulin, Nicholas G., Turgenev: A Bibliography of Books, 1843–1982 by and About Ivan Turgenev, Calgary, Alberta: Calgary University Press, 1985

Further Reading

Costlow, Jane T., Worlds Within Worlds: The Novels of Ivan Turgenev, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1990

Freeborn, Richard, Turgenev: The Novelist’s Novelist, Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1978 (original edition, 1960)

Gifford, H., “Turgenev,” in Nineteenth-century Russian Literature: Studies of Ten Russian Writers, edited by J.L.I.Fennell, Berkeley: University of California Press, and London: Faber, 1973

Granjard, Henri, Ivan Tourguenev et les courants politiques et sociaux de son temps, Paris: Institut d’fitudes Slaves, 1954

Hellgren, Ludmilla, Dialogue in Turgenev’s Novels: SpeechIntroductory Devices, Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1980

Jackson, R.L., “The Root and the Flower: Dostoevsky and Turgenev: A Comparative Esthetic,” Yale Review (Winter 1974): 228–50

Jackson, R.L, “The Turgenev Question,” Sewanee Review 93 (1985):300–09

Kagan-Kans, Eva, Hamlet and Don-Quixote: Turgenev’s Ambivalent Vision, The Hague: Mouton, 1975

Ledkovsky, Marina, The Other Turgenev: From Romanticism to Symbolism, Würzburg: Jal, 1973

Lednicki, Waclaw, Bits of Table Talk on Pushkin, Mickiewicz, Goethe, Turgenev and Sienkiewicz, The Hague: Nijhoff, 1956

Peterson, Dale E., The Clement Vision: Poetic Realism in Turgenev and James, Port Washington, New York: Kennikat Press, 1975

Ripp, Victor, Turgenev’s Russia: From “Notes of a Hunter” to “Fathers and Sons”, Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1980

Schapiro, Leonard, Turgenev: His Life and Times, Oxford: Oxford University Press, and New York: Random House, 1978

Seeley, Frank Friedeberg, Turgenev: A Reading of His Fiction, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991

Waddington, Patrick, Turgenev and England, London: Macmillan, 1980; New York: New York University Press, 1981

Waddington, Patrick, Ivan Turgenev and Britain, Oxford: Berg, 1995

Walicki, A., “Turgenev and Schopenhauer,” Oxford Slavonic Papers 10 (1962):1–17

Wilson, Edmund, Introduction to Literary Reminiscences and Autobiographical Fragments by Turgenev, New York: Farrar Straus and Cudahy, 1958; London: Faber, 1959

►→ back to ►→ Encyclopedia of THE ESSAY

Please contact the author for suggestions or further informations: architects.co@gmail.com;

►→home

Table of content “united architects essays”

►→*content all sites:

MORE INFORMATION ON MY OTHER SITES:

architecture, literature, essays, philosophy, biographies

Leave a comment